KEY HIRAGA: The Elegant Life of Mr. H

Nonaka-Hill brings to Los Angeles the works of Japanese artist Key Hiraga (b. 1936 - d. 2000). The self-taught painter, a violator of convention, who briefly belonged to the Narrative Figuration movement, lived and worked in post-war, restructured Tokyo, and from 1964 to 1974, in an idealist, radicalized Paris. The Elegant Life of Mr. H, which opens on Saturday, April 12th, includes paintings and works on paper spanning from the 1950s to the 1980s, and will be on view through May 31, 2025.

Key Hiraga: Elegant Extremity

Julian Myers-Szupinska

Tumble down the rabbit-hole of Key Hiraga’s work in the late-60s and early-70s and find yourself in a comical world of swollen extremities and orifices: boobs, dicks, noses, and tongues, licking, waggling, penetrating, and pimpled. This is a mute floating world where sex, lurid and illogical, is everywhere, and biology operates according to chaotic rules. Bodies might interpenetrate, split apart, or open a window into their innards, exposing gurgling intestines or a fetus waving happily from inside a womb. A central character of this universe is Mr. K, whose goggling, bloodshot eyes and bowler hat make him an avatar of the artist himself, and whose “elegant life” these pictures describe.

From what sort of person, and history, did these wild images emit? Born in Tokyo in 1936, Hiraga’s childhood was spent in wartime, during which his family lived in Morioka, a quiet city surrounded by mountains in north Japan. Influenced by wartime comics, he developed a child’s love for art, and early on drew battle scenes for Japanese soldiers’ care packages. (1) Later, after returning to Tokyo, he designed tattoos for occupying American soldiers at a friend’s shop in Asakusa: “If they were paratroopers, I’d design a pig hanging from a parachute,” he recalled. (2) Pressed by his parents to study economics rather than art, he skipped a conventional art education. Ironically, this positioned him after graduation to participate in a late-1950s fascination among Japanese artists, especially those unaffiliated with official art societies, with Art Informel and Art Brut, European art movements focused on gestural line and influenced by art by children and the insane.

Hiraga’s early work—drawings on canvas, scratched into a surface of white oil paint—bore resemblances to Dubuffet’s work of the late 1940s and -50s. They are ineluctably flat, largely monochromatic, and sketch out lump-like bodies with spindly limbs against spotted, yellowed, stained-seeming backgrounds. Hiraga’s dead-eyed figures, though, drew equally from manga, and often sprouted word balloons chattering nonsense kanji or loopy, quasi-cursive. He soon began painting “psychological landscapes”—scorched and stormy terrains—and canvases subdivided into “windows”: discrete panels, each obeying their own scribbled logic. (3) These too drew on the example of manga but were equally inspired by Hiraga’s shocked, thrilled experience of Tokyo’s newly built public housing complexes, the result of a postwar construction boom: “Every window had the same shape, but inside, completely different lives were unfolding . . . it felt like America.” (4)

Hiraga’s talent was noticed. He was soon winning young-artist prizes, including an award sponsored by the British oil and gas company Shell in 1963, and the grand prize at the 3rd International Young Artists Exhibition in 1964, which included a grant for study in Paris—surely an emerging artist’s dream? Not so for Hiraga, who later mused, “I had no desire to go to Paris . . . it was like a punishment, in a way.” (5) Reluctant to leave, he spent several months in Japan, during which he married Koda Sachi and was invited by William Lieberman, then curator of Drawing and Prints at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, to participate in the museum’s exhibition New Japanese Painting and Sculpture, where he would show two oil paintings, The Day It Rained (1963), and The Window (1964). (6)

Hiraga moved to Paris in April 1965, and despite “total culture shock,” found inspiration, in the form of Pop-vivid colors—a reaction to Europe’s “darkness”—and a strong network of galleries and artists interested in his work. (7) Living with his wife in the 11th arrondissement, he frequented bars on the Boulevard Saint-Germain with a drinking buddy, the critic and curator Tadao Ogura; Hiraga would memorialize this booze-soaked era in a (possibly imaginary) art book titled Paris Drunken Dream Chronicles. (8) And he showed his work. His exhibition history lists shows at Galerie Lambert, Paris; at the Traverse Gallery in Edinburgh, Scotland, a countercultural space run by the free-love advocate Jim Haynes; and in the exhibition La Figuration Narrative at Galerie Creuze, Paris, where he would have shown alongside David Hockney, Öyvind Fahlström, and Niki de Saint-Phalle. (9) Hiraga met members of the avant-garde artists’ group CoBrA, who brokered his relationship with galleries in the Netherlands, (10) another home base for several years. The bowler-hatted Mr. K (or sometimes Mr. H) became, in the work of the next decade and more, a libertine: René Magritte’s Man in a Bowler Hat with his cock out, gawking and grinding his teeth.

Read Hiraga’s curriculum vitae over the next decade and find an artist swamped with opportunities, showing his work in Amsterdam, Kyoto, Milan, Tokyo, São Paulo, and more, (11) whose work filled gallery windows in Paris, (12) but who could still be described as a “cheerful person, often short of money.” (13) His work in this period ramped up, both in sheer number of works produced, and in the increasingly radical pulverization of the figures it depicted. Mr. K’s gaga male sexuality came unmoored, mashed together with its objects, mechanical. There is violence here: body horror, razor-sliced heads, severed dick-snakes. Bodies merge and mutate, not always happily. Sexual attributes float free from gendered owners, multiply, and transmute. Mr. K wears a condom on his elongated cock-nose, wears garters, has boobs and a vulva. The floating world gains a self-reproducing autonomy, free of any subject that might be affirmed or denied. Cartoon spermatozoa wriggle and spew from priapic pipes. Eyeballs lunge from their sockets, sperm-like. The elegant life becomes ever-more-polymorphous, a science-fictional sex-machine.

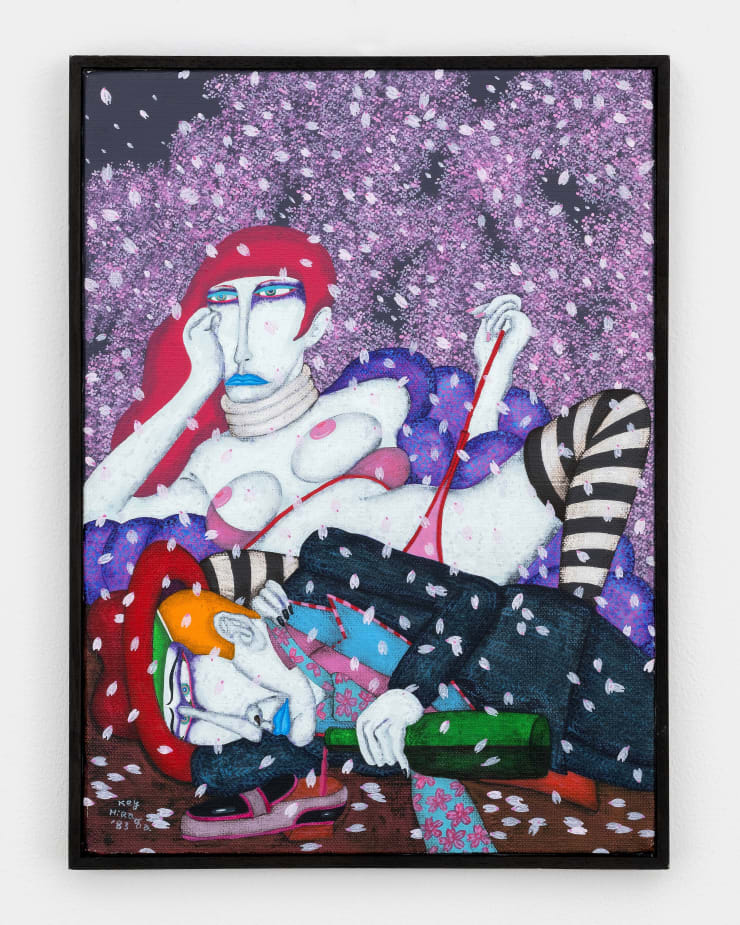

Eventually, this elegant life found limits—whether in the anarchy of the aesthetic (how much farther could he take it?) or in the sensorium of a human body that without infinite resources cannot live forever in a drunken dream. In the mid-1970s, Hiraga’s paintings, which until then had happened in a flat non-space, began to impose a reality principle, the third dimension. His figures were suddenly somewhere: in cars or rooms, posing on beaches, stalking through a red-light district. After a decade-and-more of travels, he returned, in 1977, permanently to Japan. The bodily chaos of the previous years coalesced into figures and figure-groups drawing on historical genres, like ukiyo-e, and artists, like Hiroshige. (14) Prostitutes and gangsters glare, with stylized, self-consciously Japanese accoutrements: folding screens and tatami mats, cherry blossoms, and fugu.

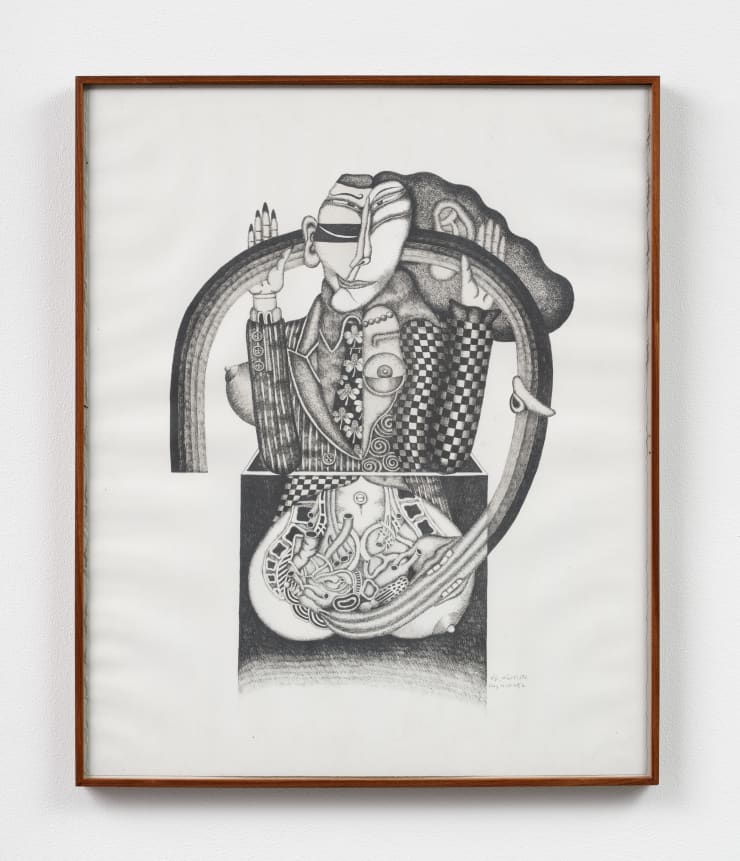

Conservative? Maybe—relatively. The old radicalism still cropped up from time to time, as in the 1981 lithograph series Hako, where the titular box offers a lens onto snarling anatomical chaos inside the new figures, who smoke and leer as they are splayed or pulled apart. It winks at the edges of his brothel scenes. But seen within the arc of a life—Hiraga died in 2000 shortly after moving to Hakone-Yumoto, a village in Kanagawa prefecture—one might wonder, dialectically, if the visceral chaos of his international years might likewise have belonged to a place: The West. The bowler hat, after all, is a Victorian invention, adopted in late-19th century Japan as a stylistic signifier of modernity. Follow this line of thought and find in Hiraga’s pre-Paris life a constant interpenetration of Japan and the hard-and-soft-power of the West: tattoos for occupying soldiers, a craze for Art Informel, new American-style public housing, an art award from British oil company, the dreaded grant to study in Paris, “total culture shock.” (15) Relocated to the cultural heart of an empire, who can blame a cheerful Mr. K for going apeshit? And who is to say whether this chaos was not, in its way, a sort of realism? The irony of his elegance should not be lost on us.

(1) Key Hiraga, “Artist Interview,” by Hikari Koike, in Modern Painter: Exhibition of the Avant-Garde Fiction Paintings of Key Hiraga, exhibition catalogue (Hiratsuka Museum of Art, 2000), 12–16. As translated by Chie Taino.

(2) Hiraga, “Artist Interview.”

(3) Hiraga, “Artist Interview.”

(4) Hiraga, “Artist Interview.”

(5) Hiraga, “Artist Interview.”

(6) The New Japanese Painting and Sculpture was organized by Lieberman and Dorothy C. Miller, the museum’s senior curator of Painting and Sculpture, and was open from October 19, 1966, to January 2, 1967. The museum acquired Hiraga’s Windows for its permanent collection in 1967.

(7) Hiraga, “Artist Interview.”

(8) As described by Japanologist and art historian Inge Klompmakers in The Elegant Life of Key Hiraga: A Japanese Artist in Europe, 1965–1974, exhibition catalogue (The Mayor Gallery, 2008), 8–10. Describing his Paris years, Hiraga reminisced, “Time flies. The days just go by so quickly. That’s why I titled my art book Paris Drunken Dream Chronicles. It really felt like an instant.” Hiraga, “Artist Interview.” The art book’s existence is unconfirmed.

(9) Klompmakers narrates Hiraga’s participation in La Figuration narrative (The Elegant Life, 10) but misdates it to 1966. Organized by the French critic and curator Gérald Gassiot-Talabot, La Figuration narrative dans l’art contemporain appeared at Galerie Creuze, Paris, October 1–29, 1965; Hiraga’s name does not appear on the poster for the show. Hiraga may have been a late addition—he arrived in Paris in April—or he may have been added to later editions of the show as it traveled. Hiraga’s correspondence with Gassiot-Talabot seems to begin in 1966.

(10) According to Klompmakers, he became acquainted with the CoBrA artist Corneille, who introduced him to Gallery T, Haarlem, the Netherlands (The Elegant Life, 10). Inaugurated in 1966, Gallery T was run by the Dutch comics artist Frans Funke Küpper and his wife Rithé and specialized in the New Figuration movement. See “Frans Funke Küpper,” Lambiek Comiclopedia, last updated September 7, 2024, https://www.lambiek.net/artists/f/funke_kupper_f.htm.

(11) Hiraga was one of seven artists chosen by Tadao Ogura to represent Japan at the 10th São Paulo Biennial. See Ogura, Japao: 10 Bienal de Sao Paulo 1969: Key Hiraga, Kozo Mio, Hotoshi Maeda, Keiji Usami, Tomio Miki, Hisayuki Mogami, Kazuo Yuhara, exhibition catalogue (Bienal de Sao Paulo and Kokusai Bunka, 1969).

(12) Yutaka Sasaki, “Key Hiraga: Endless Mystery,” in Modern Painter: Exhibition of the Avant-Garde Fiction Paintings of Key Hiraga, exhibition catalogue (Hiratsuka Museum of Art, 2000), 9. As translated by Chie Taino.

(13) This characterization relies on Klompmakers’s reading of Hiraga’s correspondence with Gallery T (The Elegant Life, 10). She writes, “more than once he asked Gallery T for an advance payment or a loan.”

(14) For example, Klompmakers, 11 n.18, traces fireworks in the background of a 1990 painting by Hiraga to a scene in Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1858). See also the description offered by Bokushin Gallery director Yasuaki Niimi in “The Ultimate Aesthetic of the Ordinary,” in Modern Painter, 11. As translated by Chie Taino.

(15) Hiraga, “Artist Interview.”

Key HiragaCherry Blossoms in the Night at Koiso, 1983Acrylic on canvas13 x 9 1/2 in (33 x 24 cm)

Key HiragaCherry Blossoms in the Night at Koiso, 1983Acrylic on canvas13 x 9 1/2 in (33 x 24 cm)

13 3/4 x 10 1/8 x 1 in framed (34.9 x 25.7 x 2.5 cm framed) Key HiragaTo Where, 1973Acrylic on canvas34 7/8 x 45 5/8 in (88.5 x 115.8 cm)

Key HiragaTo Where, 1973Acrylic on canvas34 7/8 x 45 5/8 in (88.5 x 115.8 cm)

41 x 51 5/8 x 2 3/8 in framed (104 x 131 x 6 framed cm) Key HiragaUntitled, 1971Acrylic on canvas21 1/4 x 17 3/4 in (54 x 45 cm)

Key HiragaUntitled, 1971Acrylic on canvas21 1/4 x 17 3/4 in (54 x 45 cm)

22 1/8 x 18 5/8 x 1 1/4 in framed (56.2 x 47.3 x 3.2 cm) Key HiragaUntitled, 1971Acrylic on canvas21 5/8 x 18 1/8 in (55 x 46 cm)

Key HiragaUntitled, 1971Acrylic on canvas21 5/8 x 18 1/8 in (55 x 46 cm)

22 1/8 x 18 5/8 x 1 1/4 in framed (56.2 x 47.3 x 3.2 cm framed) Key HiragaThe Elegant Life of Mr. K, 1971Acrylic on canvas51 1/8 x 63 3/4 in (130 x 162 cm)

Key HiragaThe Elegant Life of Mr. K, 1971Acrylic on canvas51 1/8 x 63 3/4 in (130 x 162 cm)

51 5/8 x 61 1/4 x 1 1/4 in framed (131.1 x 155.6 x 3.2 cm) Key HiragaThe Elegant Life of Mr. H, 1973Acrylic on canvas17 7/8 x 20 7/8 in (45.5 x 53 cm)

Key HiragaThe Elegant Life of Mr. H, 1973Acrylic on canvas17 7/8 x 20 7/8 in (45.5 x 53 cm)

19 1/2 x 22 1/2 x 2 in framed (49.5 x 57.1 x 5.1 cm framed) Key HiragaUntitled, 1989Mixed media on paper15 x 18 1/8 in

Key HiragaUntitled, 1989Mixed media on paper15 x 18 1/8 in

38 x 46 cm Key HiragaUntitled, 1992Mixed media on paper12 7/8 x 16 1/2 in

Key HiragaUntitled, 1992Mixed media on paper12 7/8 x 16 1/2 in

32.7 x 41.8 cm Key HiragaTea Ceremony at Yesterday's Hermitage, 1984Mixed media on paper15 x 17 3/4 in

Key HiragaTea Ceremony at Yesterday's Hermitage, 1984Mixed media on paper15 x 17 3/4 in

38 x 45 cm Key HiragaGin Fizz by Mr. Q, 1988Mixed media on paper17 3/8 x 13 in

Key HiragaGin Fizz by Mr. Q, 1988Mixed media on paper17 3/8 x 13 in

44 x 33 cm Key HiragaThe Woman in the Window, 1975Acrylic on canvas10 5/8 x 8 1/2 in (27 x 21.6 cm)

Key HiragaThe Woman in the Window, 1975Acrylic on canvas10 5/8 x 8 1/2 in (27 x 21.6 cm)

16 7/8 x 14 3/4 x 1 1/2 in framed (43 x 37.6 x 3.7 cm framed) Key HiragaSoap bubble, 1975Acrylic on canvas17 3/4 x 21 in (45 x 53.5 cm)

Key HiragaSoap bubble, 1975Acrylic on canvas17 3/4 x 21 in (45 x 53.5 cm)

22 5/8 x 25 5/8 x 1 5/8 in framed (57.5 x 65 x 4 cm framed) Key HiragaRose and Candy III, 1978Acrylic on canvas10 7/8 x 8 3/4 in (27.5 x 22.2 cm)

Key HiragaRose and Candy III, 1978Acrylic on canvas10 7/8 x 8 3/4 in (27.5 x 22.2 cm)

12 3/8 x 10 1/2 x 1 5/8 in framed (31.4 x 26.7 x 4.1 cm) Key HiragaInside the Car, 1981Acrylic on canvas16 x 12 1/2 in (40.5 x 31.8 cm)

Key HiragaInside the Car, 1981Acrylic on canvas16 x 12 1/2 in (40.5 x 31.8 cm)

22 x 18 1/8 x 1 3/4 in framed (56 x 46.1 x 4.5 cm framed) Key HiragaThe Elegant Life of Mr. H, 1967Mixed media on paper10 5/8 x 8 5/8 in

Key HiragaThe Elegant Life of Mr. H, 1967Mixed media on paper10 5/8 x 8 5/8 in

27 x 22 cm Key HiragaThe Elegant Life of Mr. H, 1967Oil on canvas25 5/8 x 21 1/4 in (65 x 54 cm)

Key HiragaThe Elegant Life of Mr. H, 1967Oil on canvas25 5/8 x 21 1/4 in (65 x 54 cm)

26 1/2 x 22 1/8 x 1 1/8 in framed (67.3 x 56.2 x 2.9 cm framed) Key HiragaUntitled, 1967Ink and acrylic on paper9 5/8 x 11 3/4 in

Key HiragaUntitled, 1967Ink and acrylic on paper9 5/8 x 11 3/4 in

24.5 x 30 cm Key HiragaUntitled, 1967Oil on canvas28 3/4 x 23 5/8 in (73 x 60 cm)

Key HiragaUntitled, 1967Oil on canvas28 3/4 x 23 5/8 in (73 x 60 cm)

29 1/2 x 24 1/2 x 1 1/2 in framed (74.9 x 62.2 x 3.8 cm framed) Key HiragaUntitled, 1968Oil on canvas18 1/8 x 21 5/8 in (46 x 55 cm)

Key HiragaUntitled, 1968Oil on canvas18 1/8 x 21 5/8 in (46 x 55 cm)

19 3/4 x 23 3/8 x 1 3/8 in framed (50.2 x 59.4 x 3.5 cm framed) Key HiragaHako, 1981Lithograph27 1/2 x 22 1/2 in (70 x 57 cm)

Key HiragaHako, 1981Lithograph27 1/2 x 22 1/2 in (70 x 57 cm)

28 3/8 x 23 1/4 x 1 in framed (72.2 x 59.2 x 2.5 cm framed) Key HiragaHako, 1981Lithograph27 1/2 x 22 1/2 in (70 x 57 cm)

Key HiragaHako, 1981Lithograph27 1/2 x 22 1/2 in (70 x 57 cm)

28 3/8 x 23 1/4 x 1 in framed (72.2 x 59.2 x 2.5 cm framed) Key HiragaHako, 1981Lithograph27 1/2 x 22 1/2 in (70 x 57 cm)

Key HiragaHako, 1981Lithograph27 1/2 x 22 1/2 in (70 x 57 cm)

28 3/8 x 23 1/4 x 1 in framed (72.2 x 59.2 x 2.5 cm framed) Key HiragaHako, 1981Lithograph27 1/2 x 22 1/2 in (70 x 57 cm)

Key HiragaHako, 1981Lithograph27 1/2 x 22 1/2 in (70 x 57 cm)

28 3/8 x 23 1/4 x 1 in framed (72.2 x 59.2 x 2.5 cm framed)

Related artist

Artist Exhibited:

Ulala Imai

Kazuo Kadonaga

Kentaro Kawabata

Zenzaburo Kojima

Kisho Kurokawa

Tadaaki Kuwayama

Toshio Matsumoto

Keita Matsunaga

Yutaka Matsuzawa

Kimiyo Mishima

Kunié Sugiura

Takuro Tamayama

Tiger Tateishi

Sofu Teshigahara

Shomei Tomatsu

Wataru Tominaga

Hosai Matsubayashi XVI

Kansuke Yamamoto

Masaomi Yasunaga

Exhibitions:

-2025-

Sea of Mud, Wall of Flame: Satoru Hoshino and Masaomi Ysunaga

KEY HIRAGA: The Elegant Life of Mr. H

-2024-

KYOKO IDETSU: What can an ideology do for me?

KENTARO KAWABATA / BRUCE NAUMAN

SAORI (MADOKORO) AKUTAGAWA: CENTENARIA

Keita Matsunaga : Accumulation Flow

-2023-

NONAKA-HILL ♥ TATAMI ANTIQUES: A holiday sale of unique objects from Japan

TAKASHI HOMMA : REVOLUTION No.9 / Camera Obscura Studies

TATSUMI HIJIKATA THE LAST BUTOH: Photographs by Yasuo Kuroda

Kiyomizu Rokubey VIII: CERAMIC SIGHT

Masaomi Yasunaga: 石拾いからの発見 / discoveries from picking up stones

SHUZO AZUCHI GULLIVER ‘Synogenesis’

Koichi Enomoto: Against the day

Tatsuo Ikeda / Michael E. Smith

Hiroshi Sugito: the garden with Zenzaburo Kojima

Zenzaburo Kojima: This very green

Tomohisa Obana: To see the rainbow at night, I must make it myself

Daisuke Fukunaga: Beautiful Work

- 2021 -

Natsuyasumi: In the Beginning Was Love

Takashi Homma: mushrooms from the forest

– 2020 –

Hosai Matsubayashi XVI & Trevor Shimizu

Sterling Ruby and Masaomi Yasunaga

– 2019 –

A show about an architectural monograph

Yutaka Matsuzawa

Yutaka Matsuzawa through the lens of Mitsutoshi Hanaga

Takuro Tamayama & Tiger Tateishi

Kunié Sugiura

Masaomi Yasunaga

Miho Dohi

Wataru Tominaga

Naotaka Hiro

Parergon: Japanese Art of the 1980s and 1990s

Tadaaki Kuwayama

– 2018 –

Toshio Matsumoto

Kentaro Kawabata

Kansuke Yamamoto

Kazuo Kadonaga: Wood / Paper / Bamboo / Glass

Press:

-2025-

OCULA, Kaoru Ueda

Galerie, Kaoru Ueda

Ceramic Now, Satoru Hoshino and Masaomi Yasunaga

ARTFORUM, Sawako Goda

Artillery Magazine, Sawako Goda

-2024-

Artsy, Nonaka-Hill

Richesse, Nonaka-Hill Kyoto

Bijutsutecho, Nonaka-Hill Kyoto

The Art Newspaper, Nonaka-Hill Kyoto

Meer, Kyoko Idetsu

Bijyutsutecho, Masaomi Yasunaga

Switch, Masaomi Yasunaga

ARTnews JAPAN, Masaomi Yasunaga

Richesse, Masaomi Yasunaga

Art Basel, Daisuke Fukunaga, Imai Ulala

Art Basel, Kazuo Kadonaga, Sofu Teshigahara

-2023-

ADF webmagazine, Yasuo Kuroda, Tatsumi Hijikata

e-flux, Sanya Kantarofsky, Yasuo Kuroda

Los Angeles Times, Kenzi Shiokava

Artillery, Masaomi Yasunaga

Contemporary Art Daily Shuzo Azuchi Gulliver

- 2022 -

Contemporary Art Daily, Tomohisa Obana

ARTE FUSE, Daisuke Fukunaga

Contemporary Art Daily, Daisuke Fukunaga

Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles (Carla), Daisuke Fukunaga

What's on Los Angeles, Daisuke Fukunaga

Hyperallergic, Daisuke Fukunaga

Artillery, Kentaro Kawabata

Larchmont Buzz, entaro Kawabata

- 2021 -

Art Viewer, Natsuyasumi: In the Beginning Was Love

Hyperallergic, Natsuyasumi: In the Beginning Was Love

Art Viewer, Takashi Homma

Hyperallergic, Busy Work at Home

Art Viewer, Busy Work at Home

Hyperallergic, Ulala Imai

Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles (Carla), Ulala Imai

Contemporary Art Daily, Ulala Imai

artillery, Ulala Imai

Special Ops, Ulala Imai

Art Viewer, Ulala Imai

artillery, Matsubayashi & Trevor Shimizu

– 2020 –

Ceramic Now, Sterling Ryby and Masaomi Yasunaga

Hypebeast, Sterling Ryby and Masaomi Yasunaga

Art Viewer, Sterling Ruby and Masaomi Yasunaga

Air Mail, Sterling Ruby and Masaomi Yasunaga

Los Angeles Times, Kaz Oshiro

ArtnowLA, Kaz Oshiro

What's on Los Angeles, Kaz Oshiro

KCRW, Kaz Oshiro

Tique, Kaz Oshiro

Contemporary Art Daily, Kaz Oshiro

Art Viewer, Kaz Oshiro

Contemporary Art Daily, Sofu Teshigahara

Art Viewer, Sofu Teshigahara

KCRW, Sofu Tsshigahara

Hyperallergic, Nonaka-Hill

Los Angeles Times, Keita Matsunaga

– 2019 –

Los Angeles Times, Tatsumi Hijikata

Art Viewer, Tatsumi Hijikata, Eikoh Hosoe

Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles, Tatsumi Hijikata, Eikoh Hosoe

ArtAsiaPacific, Yutaka Matsuzawa

Los Angeles Times, Tatsumi Hijikata

AUTRE, Tatsumi Hijikata, Eikoh Hosoe

Los Angeles Times, Nonaka-Hill

ARTFORUM, Takuro Tamayama, Tiger Tateishi

Art Viewer, Takuro Tamayama, Tiger Tateishi

KCRW, Nonaka-Hill

LA WEEKLY, Nonaka-Hill

AUTRE, Takuro Tamayama, Tiger Tateishi

ArtsuZe, Takuro Tamayama, Tiger Tateishi

ARTFORUM, Review: Tadaaki Kuwayama, Rakuko Naito

Art Viewer, Masaomi Yasunaga, Kunié Sugiura

Los Angeles Times, Masaomi Yasunaga

KQED, Tadaaki Kuwayama, Rakuko Naito

Contemporary Art Daily, Naotaka Hiro, Wataru Tominaga, Miho Dohi

Los Angeles Times, Miho Dohi

Los Angeles Review of Books, Miho Dohi

Bijutsu Techo, Naotaka Hiro, Wataru Tominaga, Miho Dohi

Art Viewer, Miho Dohi

Art & Object, Parergon

COOL HUNTING, Felix Art Fair

Art Viewer, Tadaaki Kuwayama

artnet news, Nonaka-Hill

Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles (Carla), Tadaaki Kuwayama

– 2018 –

Art Viewer, Kentaro Kawabata

Contemporary Art Daily, Kazuo kadonaga

Los Angeles Times, Kazuo Kadonaga

ARTFORUM, Kazuo Kadonaga

Contemporary Art Daily, Shomei Tomatsu

KCRW, Kimiyo Mishima, Shomei Tomatsu

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Find out more about cookies.